Krystyna Koziewicz

Zgaduj zgadula!

Jak nazywa się miejscowość w której znajduje się 1 sklep spożywczy, 13 galerii artystycznych i 1 Muzem Sztuki?

***

Raten Sie mal!

Wie heißt die Stadt mit 1 Lebensmittelladen, 13 Kunstgalerien und 1 Kunstmuseum?

Krystyna Koziewicz

Zgaduj zgadula!

Jak nazywa się miejscowość w której znajduje się 1 sklep spożywczy, 13 galerii artystycznych i 1 Muzem Sztuki?

***

Raten Sie mal!

Wie heißt die Stadt mit 1 Lebensmittelladen, 13 Kunstgalerien und 1 Kunstmuseum?

Monika Wrzosek-Müller

Lublin – Tamara Łempicka

Der Ausflug nach Lublin, hauptsächlich zu der Ausstellung, war schön, lehrreich und interessant. Schon die Schnellstraße S 17, auf der wir gefahren sind, erfüllte alle europäischen Standards, mehr noch, war besser als die meisten „Superstrade“ in Italien, gepflegt auch rundherum und kostenlos. Ich habe die Gegend um Lublin und Nałęczów als Kind öfters gesehen, auch von Kazimierz Dolny aus und auch später; sie hat sich so sehr entwickelt, verändert, es wurden prächtige Häuser gebaut, vielfältige Obstplantagen angelegt. Klar, das ist auch der Teil Polens, der die besten Lössböden hat; trotzdem hat mich das Ausmaß des Fortschritts und der Entwicklung überrascht. Für meine Begriffe hat sich da viel mehr verändert als in unserer Uckermark in Brandenburg.

Unterwegs achteten wir auf die vorbeifahrenden Lastwagen; es fuhren nur einige wenige mit weißrussischen Kennzeichen, die meisten hatten ukrainische, russische haben wir überhaupt keine gesehen. Es gab aber viele ukrainischen Personenwagen in beiden Richtungen.

Lublin begrüßte uns mit herrlichem Wetter, mit einer sehr aufgeräumten, renovierten Altstadt, mit vielen Touristen, erstaunlich vielen auch ukrainischen Touristen, die mit ihren Autos da waren; sie machten nicht den Eindruck von Flüchtlingen. Einige von ihnen, vor allem Frauen, begleiteten uns in die Ausstellung weiter, sie filmten alles und sahen sich die Exponate erstaunlich eingehend und interessiert an. Ich fragte mich schon sowieso, warum Lublin, dann vielleicht auch ukrainische Wurzeln bei Tamara Lempicka, doch das Einzige was ich finden konnte, waren eher russische Verbindungen und Verwandtschaften ihres Vaters. Das Lubliner Schloss, das mich bei früheren Besuchen immer an eine aus Pappmaschee aufgestellte Kulisse erinnert und eher abgeschreckt hatte, war sehr sorgfältig restauriert. Im Innenhof sind der Turm und die Kapelle zu besichtigen (Überreste der alten Burg). Nichts deutete auf den Krieg hin, der doch nicht weit, fast um die Ecke weitertobt.

Also der Titel der Ausstellung „Die Frau unterwegs“ passt vielleicht am besten zu dieser doch sehr faszinierenden Frau. Sie hat in ihrem Leben meistens, so scheint mir, das gemacht, was sie wollte, und vor nichts hatte sie Angst, natürlich half ihr das Talent. Das Interesse an ihr und ihrem Werk – ich erinnere mich an eine Ausstellung in Mailand, 2006 im Palazzo Reale, wo sie Tamara de Lempicki genannt wurde; die Mailänder Ausstellung habe ich nicht gesehen, wohl aber die Plakate, die in der ganzen Stadt aushingen, und die langen Schlangen vor dem Eingang – beruht vielleicht auch auf ihrer Art der Selbstinszenierung, auf ihrem Habitus einer Diva, die wohl auch eine gute Künstlerin war; eine coole, schöne Frau, das spielte sie alles sehr gekonnt aus, auch ihre Herkunft, auch ihren Namen. Sie positionierte sich irgendwo zwischen Peggy Guggenheim und den vielen Filmdiven des damaligen Hollywood und ihr Bild trug zum Teil bestimmt zu dem Erfolg bei, den sie in den dreißiger und vierziger Jahren hatte.

Geboren wurde Tamara Rozalia Gurwik-Górska laut einiger Quellen in Warschau am 16. Mai 1898, doch manche sprechen von Moskau und einem zwei Jahren späteren Geburtsdatum. Ihre Eltern gehörten einer Elite an, die in Warschau, Moskau und St. Petersburg zu Hause war, doch immer wieder auch länger in anderen Teilen des Europas weilte, so in der Schweiz, in Italien und in Paris. Ihr Vater wird als reicher russischer Jude, Kaufmann oder Industrieller, beschrieben; er starb bald nach ihrer Geburt. Die Mutter stammte aus einer wohlhabenden polnisch-katholischen Familie, die zahlreiche Beziehungen zu berühmten Künstlern wie Ignacy Paderewski oder Artur Rubinstein pflegte. Sie wuchs eher bei den Großeltern und in Internaten auf. Irgendwann übersiedelte sie dann nach St. Petersburg, wohnte bei ihrer Tante und deren Mann, der Familie Stifter, in einer luxuriösen Residenz. Beim ersten Ball, den sie als ganz junge Frau besuchen durfte, lernte sie ihren späteren Mann Thadé Lempicki kennen. Die beiden heirateten schnell und Tamara wurde bald auch Mutter einer Tochter – Kizette, die sie später oft porträtieren wird. Leider ändert sich die Situation in Petersburg für sie schnell zum Schlechten, die Verwandten emigrierten nach Dänemark. Tadeusz wurde im Winter 1918 verhaftet und in ein Gefängnis gesteckt; Tamara nutzte ihre Bekanntschaft zum schwedischen Konsul und beschaffte falsche Dokumente auch für ihren Mann, sie reisten erst einmal nach Kopenhagen, dann nach Warschau und bald schon nach Paris. Nach einigen dort unter schwierigen Umständen verbrachten Monaten half ihr die Familie, ihre Schwester Adrianna Górska überredete sie zum Studium an der Académie Ranson. Seitdem scheint das Leben für Tamara wieder buntere Farben angenommen zu haben. Durch Vermittlung der Schwester stellte sie ihre Bilder aus; sie wurden von der Kritik warm und positiv aufgenommen. Bald kam es auch zur ersten Reise nach Italien, auf die viele weitere folgen sollten. Sie lernte einflussreiche, künstlerisch interessierte Italiener kennen, flirtete mit einigen von ihnen und wurde in der italienischen Szene bekannt und als Künstlerin anerkannt. Die schon vorher angespannten Beziehungen zu ihrem Mann verschlechterten sich, so dass sie 1928 auseinandergingen. Tadeusz heiratete bald seine neue Liebe, Tamara lernte den ungarischen Baron Raoul Kuffner kennen. In diesen Jahren entstanden Bilder wie „Mein Porträt“ oder auch „Die Frau im grünen Bugatti“, das die Titelseite einer Zeitschrift zierte. Es wurde zum Symbol einer freien, selbstbestimmten Frau und auch eine Ikone des art déco. 1934 heiratete sie zum zweiten Mal, den Baron, zog nach Wien und Budapest, besuchte mehrmals Italien, reiste auch tiefer in den Süden, es zog sie nach Afrika und in den Nahen Osten. Sie suchte die Wärme und das Leben, das ihr eigenes ihr nicht ausreichend gab. Als der Zweite Weltkrieg ausbrach, verließen die Kuffners Europa, sie fuhren nach Amerika. Sie malte dort die Damen der Gesellschaft, er floh als Jude vor dem Naziterror. In Amerika wurden sie jedoch nicht an einem Ort sesshaft, sie besichtigten, wohnten in New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Miami aber auch auf Cuba. Auch ihre Töchter kamen nach Amerika. Erst ab 1949 kehrte Tamara mehrmals nach Europa, Italien, Paris zurück. Nach dem Tod ihres Mannes 1962 zog sie zu ihrer Tochter Kizette, die in Huston wohnte. Doch lange hielt sie an einem Ort und wahrscheinlich mit der Familie nicht aus und zog nach Cuernavaca in Mexico, in die Stadt des ewigen Frühlings. 1980 stirbt sie auch dort und ihre Asche wurde am Vulkan Popocatépetl verstreut.

Ihr Leben hat sie an verschiedene Orte geführt, sie blieb nie länger irgendwo, war getrieben von ihren eigenen Ansprüchen oder vom Schicksal? Trotzdem führte sie ein gesellschaftlich sehr erfüllendes Leben; so kam sie auch an ihre Aufträge, meistens durch Mundpropaganda. Sie malt des Öfteren Damen der höheren Gesellschaft, damit verdiente sie genug Geld, um für sich, aber auch für ihre Familie zu sorgen. Vor allem die Bilder mit den klaren, eindeutigen Farben, die mit Schatten und Licht spielten, blieben ihr Markenzeichen, das madonnenhafte Blau, das klare Hoffnungsgrün. Irgendwann war sie eine der bestbezahlten Künstlerinnen der Welt. Schwer wog bestimmt, dass ihre Versuche in anderen Stilrichtungen nie erfolgreich waren. Sie wandte sich auch anderen Themen zu, versuchte Landschaften, Stillleben zu malen; an ihre glorreichen Erfolge der art déco-Zeit konnte sie aber nicht mehr anknüpfen.

Für mich bleibt sie die Ikone einer Zeit, in der das Gefühl der Schönheit mit der Einfachheit zusammenging, in der alles: die Architektur, die Inneneinrichtung, die Gegenstände, alles den Wunsch äußerte, das Schöne zu kultivieren und zu prämieren. Die Ausstellung bringt das eben auch zusammen, zeigt die Einrichtung ihres Appartements und Ateliers in Paris, auch Gegenstände, die sie benutzt hatte, werden ausgestellt. So ergibt sich nicht nur durch ihre Gemälde ein Bild der ganzen Person, nur so kann man sich ihr annähern und sie besser verstehen.

Jacek Krenz

Wspomnienia z lat 50. i 60. – kolejny fragment z przygotowywanej do wydania ksiązki: Jacek Krenz „Latem w Jastarni”

Zimowy kontrapunkt

Pewnej zimy, wiedzeni nostalgią, wybraliśmy się z Michałem Ozdowskim do Jastarni. Gdy pociąg wjeżdżał na półwysep, odnieśliśmy wrażenie, że to statek uwięziony na zamarzniętym morzu. Zatoka i podmokłe łąki pokryte były lodem. Jakby wszystko usnęło, ścięte mrozem. Unieruchomione.

Gdy wysiedliśmy w Jastarni, zobaczyliśmy chaty przycupnięte pod śniegiem i nisko ścielące się dymy z kominów ponad nimi. Wilgotny wiatr znad sztormowego morza pokrył szyby lodowymi kwiatami. Pusto, tu i ówdzie ktoś przemykał, opatulony. Wszystko pozamykane, stragany pozabijane deskami. Jedynie kino „Żeglarz” ciągle działało i restauracja „Meduza” na Portowej, gdzie rozgrzaliśmy się szklankami gorącej herbaty, wzmocnionej wysokoprocentową wkładką. Znaleźliśmy jakiś nocleg. Zimno. W nieprzeniknionej czerni nocy za oknem tylko pełgające gdzieniegdzie pojedyncze światełka.

Zima to był trudny czas dla rybaków. Mniejsze łodzie wyciągano na brzeg, kutry z zamarzniętego portu przeprowadzano na stałe do Helu. Praca bowiem nie ustawała. Co wieczór rybacy jechali do Helu pociągiem, skąd o świcie wypływali na połów. Koło południa, po rozładowaniu ładunku, wracali do domu na obiad i krótki odpoczynek, by na noc znów wyruszyć w drogę.

Na brzegu zwały spiętrzonej sztormem morskiej wody, skute lodem. W mroźnej ciszy nawet morze przestawało falować, oddychać. Tylko krzyk mew i sygnały buczka mgłowego brzmiały niczym obietnica letniego ożywienia, które kiedyś przecież nadejdzie.

Granat zachmurzonego nieba, antracytowa tafla zatoki i sine z zimna wszechobecne morze. Mocny kontrast z bielą śniegu, żadnych półtonów – gotowy krajobraz do niemal monochromatycznej akwareli, tak różnej od swojej kolorowej wakacyjnej wersji…

Monika Wrzosek-Müller

Żyrardów eine ehemalige Musterstadt der Leinenindustrie

An die Leinenvorhänge in meinem Kinderzimmer erinnere ich mich sehr gut. Das Orange war leuchtend und die grob gewebte Struktur ließ auch immer die Sonne durchscheinen. Mir wären etwas enger, dichter gewebte Stoffe lieber gewesen, hinter denen man sich besser verstecken und etwas mehr Schatten haben könnte. Doch diesen Leinen gab es zu kaufen und es war auch bunt, farbenfroh, im Gegensatz zu der grauen, wirklich grauen Wirklichkeit. Damals habe ich gar nicht daran gedacht, dass sich die Leinenfabriken nicht weit von Warschau befanden und der Stoff dort hergestellt wurde, deshalb auch erhältlich war. Doch die Farbigkeit und die schönen Muster sind mir immer noch in Erinnerung; die Vorhänge wurden dann im Lauf der Jahre in Kissenbezüge umgenäht. Später, als Teenager, hatte ich auch ein langes Kleid aus Leinen, exakt aus dem Leinenstoff für Kartoffelsäcke – grob, naturfarben, das Kleid lang, mit Fransen unten, sehr herausfordernd, vor allem für meine Eltern. Ansonsten hielten sie sehr an polnische Produkte, und Leinen war ein solches.

Jetzt, an dem bisher einzigen schönen Wochenende seit Weihnachten, haben wir von Warschau aus einen Ausflug nach Żyrardów unternommen. Die Stadt liegt etwa 45 Km entfernt von der Hauptstadt, in südwestliche Richtung. Sie ist leicht zu erreichen, sowohl von der Autobahn nach Posen aus als auch von der nach Kielce, sie liegt eben in der Mitte, in der flachen, platten masowischen Ebene, ziemlich unwirklich, als einziger geschlossener Komplex erhalten, vom Krieg einfach unberührt geblieben. Sie ist auch mit der Bahn zu erreichen, auf der Strecke nach Łódź. Schon seit 1845 hatte Żyrardów einen Bahnanschluss, es lag an der Eisenbahnstrecke Warschau-Wien.

Überhaupt kommt man in dem Städtchen nicht aus dem Staunen heraus; es stehen noch so viele Bauten aus dem 19. Jahrhundert: der alte, schöne Bahnhof im Stil eines polnischen Landhauses, mit prächtigen Kachelöfen im Wartesaal, die ganze Siedlung von süßen Arbeiterhäusern aus Backstein, mit Holzhäuschen in den Gärtchen, wo die Arbeiter Hühner hielten und Wirtschaftsräume hatten. Es ist atemberaubend, diese Holzkonstruktionen zu sehen, die ältesten aus den 1870er Jahren. Und sie existieren immer noch und werden von den jetzigen Bewohnern auch benutzt. Die Häuser sind noch nicht restauriert, werden aber weiter bewohnt. Im Zentrum der Siedlung gibt es natürlich eine imposante Pfarrkirche im neugotischen Stil, 1900-1903 erbaut; es gab mehrere Kirchen verschiedener Konfessionen, wie es auch verschiedene Nationalitäten gab, die in dem Städtchen zusammenlebten: Polen, Juden, Tschechen, Slowaken, Franzosen, Ukrainer, Russen; sogar Schotten und Engländer soll es gegeben haben. Die katholische Pfarrkirche ragt mit ihren beiden imposanten Kirchtürmen in der flachen Landschaft empor und man sieht sie schon von weitem. Vor der Pfarrkirche war früher der Marktplatz, heute eher eine Grünanlage mit Bänken und Rosenbeeten. Gegenüber, auf der anderen Seite der Hauptstraße („Straße des 1. Mai“) erhebt sehr der ganze Komplex der Fabrikanlagen mit der alten und neuen Spinnerei und der Strumpfweberei, die jetzt, gründlich saniert, in sehr interessant aussehende Lofts und Wohnungen umgewandelt wurde. Die Ausmaße dieser Bauten lassen den Besucher staunen, aber es handelte sich ja um die größte Leinenproduktionsstätte in Europa und die Strumpffabrik soll immerhin die größte im russischen Reich gewesen sein. Weitere Sehenswürdigkeiten kann man aufzählen: die alten Schulen und das Fabrikkrankenhaus, auch ein Waisenheim und ein Kindergarten haben dort Platz, es fehlte nicht einmal eine Bade- und Waschanstalt. Schließlich waren da die imposanten Gebäude der Verwaltung, das Kontor, das Magistratsgebäude; alle diese Bauten waren hauptsächlich aus rotem Backstein errichtet, was vielleicht an Łódź erinnert, aber allgemein in diesen Breitengraden nicht sehr häufig vorkam.

Das alles war mit Grünanlagen und Parks geplant worden und der Entwurf wurde auf der Weltausstellung in Paris als Mustersiedlung präsentiert. Offensichtlich war den Fabrikanten auch Kultur und Unterhaltung wichtig, schon 1913 entstand das Volkshaus Karl Dittrichs mit einer Bühne, später als Kino genutzt, und die „Ressource“, ein jetzt sehr schön restauriertes Gebäude, das als Touristeninformationszentrum, Hotel und Restaurant dient und früher eine Art englischen Club und ein Theater beherbergte. Man geht wirklich staunend herum – überrascht, dass damals so gründlich über ein Bauensemble nachgedacht wurde; z.B. wurde das Arbeiterquartier sorgsam getrennt von den Direktorenvillen errichtet. Mitten im sehr schön angelegten Park steht auch die Repräsentationsvilla von Karl Dittrich, jetzt ein Museum. Der Park mit seinen Wasserläufen und kleinen Brückchen, alten Buchen und Pavillons zum Verweilen wurde auch erst vor Kurzem instandgesetzt. Natürlich lag das Städtchen an einem Flüsschen, denn die Leinenproduktion verlangte viel Wasser. Ich habe sehr gelacht über seinen Namen: Pisia Gągolina (das Wort pisa stammt angeblich aus altpreußisch und bedeutete fließen, gągolina dagegen kommt von den Lauten, die die Gänse erzeugen).

Immer wieder dachte ich, das ist eine komplette Welt für sich, eingeschlossen, perfekt in sich stimmig; man konnte da leben, arbeiten, in die Schule gehen und nie herauskommen, nie den Ort wechseln; nur für den Handel, für den Verkauf mussten die Herren Direktoren sich in die Ferne, hinaus in die Welt draußen wagen. Die Produkte, die Leinenstoffe wurden in vielen Städten Europas verkauft. Die Fabrik betrieb Läden unter anderem in Warschau, Kalisz, Tschenstochau, Posen und St. Petersburg.

Ich lief durch die kleinen, von Bäumen gesäumten Straßen und stellte mir vor, wie es war damals, als die Fabriken noch in Betrieb waren, die Schornsteine Rauch ausspuckten, die Maschinen unheimlich lärmten, die Damen in den langen Kleidern spazierten und die Arbeiter und Arbeiterinnen (denn davon gab es viele) in graublauen Arbeitsuniformen vorbeihuschten. Die Vergangenheit ist hier sehr genau sichtbar und nachfühlbar, fast konserviert; die Zukunft mit den schönen Lofts noch sehr unsicher, gewünscht aber nicht gelebt.

Noch ein Aspekt ist mir bei dem Städtchen wichtig; ich hörte davon in Prag, da wollte ein junger tschechischer Historiker eine Arbeit darüber schreiben. Die Verbindungen zu Tschechen sind vielfältig und gehen tief. Die zweite Entwicklungsphase der Fabrikstadt, seit der Übernahme durch Dittrich und Hielle, die eben aus Nordböhmen kamen, brachte eine rasante Entwicklung und beträchtlichen Ausbau. Sie nannten ihr Unternehmen Zyrardower Manufacturen Hielle & Diettrich und beschäftigten eine Menge von Arbeitern und sorgten auch für sie. Unter den Familien, die nach Żyrardów kamen, gab viele Einwanderer aus Tschechen. In einer dieser Familien wurde 1881 Pavel Hulka geboren. Dank eines Stipendiums in Heidelberg konnte er als Publizist und später Übersetzter arbeiten, zusammen mit seiner polnischen Frau Kazimiera Laskowska gründete er die Zeitung Echo Żyrardowskie, in der er sich sehr für die Verbesserung der Arbeitsbedingungen der Arbeiter einsetzte. Vor allem aber war er als Übersetzer aus dem Tschechischen tätig. Er brachte Werke von Karel Čapek und Bozena Nemcova dem polnischen Publikum nahe, größere Bekanntheit erlangte er aber vor allem durch die Übersetzung des Romans „Der brave Soldat Schwejk“ von Jaroslav Hašek. Sein autobiografischer Roman, fast ein Tagebuch, „Mój Żyrardów“ kann als Quelle für das Geschehen während des Krieges in Żyrardów gelesen werden.

Und noch eins: warum eigentlich Żyrardów? Der Name stammt von dem französischen Techniker, später auch Ingenieur Philippe de Girard; sein Denkmal steht inzwischen vor der „Ressource“, für alle sichtbar. Nach einem sehr abwechslungsreichen Leben – er hatte für einen in Frankreich ausgeschriebenen Preis für eine Flachsspinnmaschine eine solche konstruiert, das Preisgeld aber nie bekommen – wurde er 1825 von der russischen Regierung nach Warschau geholt. Nach mehreren weiteren Stationen landete er schließlich mit seiner Erfindung in den Leinenproduktionsfabriken. Später versuchte er sich in Bergbau, Wasserbau und der Zuckerproduktion. Und da das G als ż ausgesprochen wird, kam es zum dem Ortsnamen Żyrardów.

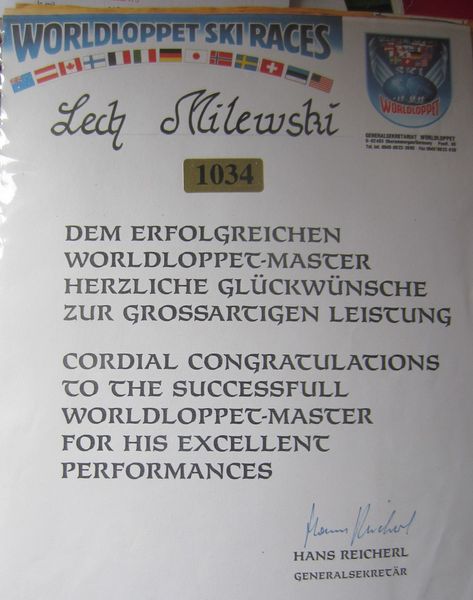

Lech Milewski

Właśnie zaczęła się Zimowa Olimpiada.

Wspominając historię zimowych olimpiad, zwróciłem uwagę na olimpiadę w Sapporo – 1972 rok.

Czyli 50 lat temu.

A co było pośrodku? Rok 1997 – moja wyprawa do Sapporo na maratony narciarskie.

Mieszkam w Australii. Po długich wędrówkach do Europy i Ameryki Północnej rozejrzałem się po bliższych okolicach. Japonia wydawała się idealna – prawie ta sama strefa czasowa, tylko 10 godzin lotu, śnieżne zimy.

Cel wyprawy – Sapporo Maraton – wyścig należący do serii WorldLoppet – KLIK.

Wyprawa na jeden wyścig?

Trochę za mało.

Google jeszcze nie było, ale udało mi się znaleźć Miyasama Maraton, tydzień po Sapporo.

To już miało dwie nogi.

Napisałem list do organizatorów Miyasama Maraton, prosząc o formularz zgłoszeniowy, pytając w jaki sposób zapłacić za uczestnictwo, jak dojechać, jak załatwić noclegi.

Po kilku tygodniach otrzymałem bardzo ugrzecznione zaproszenie – organizatorzy zapłacą za mnie wpisowe, zafundują bilet powrotny z Sapporo i zapewnią trzydniowy pobyt w hotelu.

W międzyczasie skontaktowałem się listownie z Kenichi, japońskim narciarzem, poznanym na maratonie we Francji.

Przeprosił mnie bardzo, że nie może zaoferować mi zakwaterowania u siebie, ale właśnie przenosi się do nowego domu. Ale może zaproponować mi wspólny wyjazd na maraton narciarski w Ohtaki, tam ma domek letniskowy.

Och taki, owaki – 3 maratony w 8 dni – harakiri.

Postanowiłem przylecieć do Sapporo cztery dni przed wyścigiem, żeby nieco się oswoić z warunkami i przypomnieć sobie, co to jest zima – w Australii jest w tym czasie lato w pełni.

Mieszkanie załatwiłem sobie w hostelu młodzieżowym na peryferiach miasta.

Pierwsze wrażenie po wylądowaniu w Japonii – duuuuużo ludzi.

Na lotnisku, na ulicy, w pociągu – wszędzie miałem poczucie tłoku, braku przestrzeni.

Drugie wrażenie – jadąc metrem w stronę hotelu, postanowiłem nawiązać z kimś kontakt.

Dobrze się składało, bo w wagonie była grupka uczniów w mundurkach szkolnych – na pewno znają trochę angielskiego.

Uśmiechnąłem się i zrobiłem kilka kroków w ich kierunku. Ku mojemu zaskoczeniu wszyscy rzucili się do ucieczki. Myślałem, że to jakiś żart, ale gdy sytuacja powtórzyła się, uznałem, że widocznie robię coś niewłaściwego i zrezygnowałem.

Dojechałem metrem do celu, pozostawało jeszcze przesiąść się do autobusu.

Kłopot w tym, że na przystanku autobusowym wszystkie napisy były po japońsku.

Mój cel to Miyanomoru, hotel młodzieżowy znajdował się w pobliżu skoczni narciarskiej, na której w 1972 roku Wojciech Fortuna wywalczył 6 miejsce.

To nie pomyłka, W. Fortuna zdobył złoty medal w Sapporo na dużej skoczni (Okurayama), ale kilka dni wcześniej zdobył 6 miejsce na skoczni normalnej – Miyanomori.

Niestety cała ta wiedza a nawet kartka, na której dużymi literami napisałem nazwę przystanku docelowego, okazały się nieprzydatne. Liczni podróżni czekający na przystanku na autobus zachowali się dokładnie jak uczniowie w metro – ilekroć wykonałem krok w ich kierunku, wycofywali się trzy kroki do tyłu.

W tym momencie nadjechał autobus. Podróżni ruszyli do drzwi wejściowych, w środku. Ja podbiegłem do przednich drzwi, żeby spytać kierowcę, czy dowiezie mnie do celu.

Kierowca zamknął mi drzwi przed nosem i bardzo grzecznie pokazał, że wsiada się drzwiami środkowymi.

Wsiadłem.

Tu wyjaśnię, że na mój bagaż składały się – duży plecak, mały plecaczek i torba z nartami. Teraz, z całym tym ładunkiem, musiałem się przepchać do kierowcy i spytać: Miyanomori?

Odpowiedź była przecząca. Kierowca otworzył mi drzwi.

Historia powtórzyła się jeszcze dwa razy.

Za trzecim podejściem trafiłem, dojechałem do celu…

Recepcjonista był przygotowany na mój przyjazd.

Wybiegł do mnie i na migi wytłumaczył, że buty muszę zostawić na stojaku w sieni, a w hostelu mam używać plastikowych klapek.

Dałem mu znak, żeby chwilkę poczekał i wyciągnąłem z plecaka porządne, skórzane, góralskie kapcie. Widziałem, że bardzo go to zaskoczyło, ale jak tu argumentować z góralami, z rezygnacją zaprowadził mnie do mojego pokoju.

Czteroosobowy pokój.

Pierwsza rzecz, na którą zwróciłem uwagę, to nie było w nim drzwi, w wejściu wisiały plastikowe paski.

Przypomniały mi się rozmówki angielsko-japońskie, w które zaopatrzyłem się przed wyjazdem.

Otóż wiele słów to były lekkie modyfikacje terminów angielskich:

– drzwi – door-o,

– prysznic – shower-o,

– lustro – mirror-o.

Czyżby wszystkie te urządzenia były obce Japończykom aż do połowy XX wieku?

W środku dwa piętrowe łóżka, a raczej legowiska. Bardzo szerokie.

Może dwuosobowe – pomyślałem, ale po chwili zorientowałem się, że legowisko pełni rolę łóżka i szafki. Tam rozłożyłem swoje przybory toaletowe, ubrania, itp.

Zauważyłem, że na sąsiednim legowisku leżał portfel, aparat fotograficzny, zupełna beztroska.

Nie miałem jednak czasu na rozglądanie się, recepcjonista znacząco zakaszlał i przez współlokatora poinformował mnie, że chce mi jeszcze pokazać toaletę i drogę do jadalni, gdyż za chwilę będzie kolacja.

Pokazał mi drzwi do toalety.

Skorzystałem.

Zdziwiłem się nieco, że recepcjonista nadal czekał na mnie pod drzwiami.

Za chwilę zrozumiałem… recepcjonista ze wstrętem wskazywał moje kapcie – wszak byłem w nich w toalecie, nie ma mowy żebym ich teraz używał w innych częściach hostelu.

Dopiero wtedy zauważyłem, że przy drzwiach do toalety był stojak z klapkami.

Poddałem się, założyłem plastikowe, nieco ciasne klapki i od tego czasu żyliśmy w zgodzie.

Podczas posiłku zawarłem bliższą znajomość z moim współlokatorem – Minoru.

Po pierwsze zapytał, czy mógłby spędzać ze mną więcej czasu w celu nabrania doświadczenia w angielskiej konwersacji.

Po drugie, okazało się, że też przyjechał tu, z Osaki na Sapporo Maraton, a więc okazji do konwersacji będzie sporo.

Po trzecie, bardzo delikatnie zapytał, czy chciałbym towarzyszyć mu podczas lunchu, który on ma zwyczaj spożywać w tanich restauracjach dla studentów.

3 razy TAK.

Wyjaśnił mi również rezerwę, jaką wykazywały osoby, z którymi próbowałem nawiązać konwersację.

Większość z nich zapewne rozumie po angielsku, ale nigdy nie korzystała z niego w praktycznej sytuacji.

Mieli więc obawę, że albo nie zrozumieją mojego pytania, a to byłby duży wstyd, albo, co gorsze, udzielą mi błędnej odpowiedzi, albo ja tę odpowiedź źle zrozumiem – tak czy inaczej oznaczałoby to dla nich bezsenną noc.

Nastęne trzy dni minęły bajecznie.

Każdej nocy spadało około 10 cm zmrożonego śnieżnego puchu.

Trasy narciarskie w parku były doskonale przygotowane.

W centrum Sapporo trwał właśnie Festiwal Śniegu – KLIK.

Lunche w studenckich restauracjach były bardzo pożywne – główna pozycja to ramen – KLIK.

Posiłki w hostelu były smaczne, towarzystwo sympatyczne.

W przeddzień maratonu organizatorzy urządzili spotkanie zagranicznych narciarzy…

Spotkałem tam kilku Australijczyków, którzy zwrócili mi uwagę, że w porywie patriotyzmu przyczepiłem się do nowozelandzkiej flagi.

Wreszcie dzień próby.

Organizatorzy kurtuazyjnie umieścili zagranicznych zawodników na czele stawki – ja to ten w czerwonych spodniach…

Było to dobre, ale tylko do fotografii.

START!

Od początku czuliśmy na karkach dyszenie naładowanych energią zawodników japońskiej kadry. Na szczęście za chwilę trasa wiodła pod górkę i tam nas wyprzedzili.

Przed nami 50 km olimpijskiej trasy.

Wyjaśnię, że maratony, w których uczestniczyłem do tego czasu, rozgrywane były na lokalnych, amatorskich trasach. Po raz pierwszy biegłem na trasie zaprojektowanej dla zawodowców i przyznaję, że zasłużyli na swoje zarobki.

Ohtaki.

Kenichi zawiózł mnie samochodem do swojego domku letniskowego.

Domek był niewielki. Jeden duży pokój na parterze.

Dodatkową atrakcją była łazienka, a raczej głębokie spa.

W Ohtaki są gorące źródła z leczniczą wodą, która jest dostarczana za darmo do wszystkich domów.

A więc długie moczenie się, a potem syta kolacja.

W Australii, USA i kilku innych krajach, które odwiedziłem, w przeddzień maratonu odbywało się pasta loading – czyli zjedz tyle klusek, ile tylko możesz.

W nocy zamienią się one w bardzo potrzebną energię.

Podczas spotkania narciarzy w Sapporo, stwierdziłem, że Japończycy preferują tradycyjne, solidne posiłki z przewagą protein – owoce morza.

To samo zaoferował mi Kenichi.

Pora spać.

Kenichi przesunął stół w bok i wyciągnął z szafy maty do spania.

Jestem profesorem geologii wyjaśnił i urządzam w tych okolicach praktyki dla studentów. W tym pokoju czasem nocuje na matach 12 osób.

Rano Kenichi schował maty i nakrył stół do śniadania.

Tym razem zdecydowałem zjeść śniadanie jak narciarz z Australii – owsianka. Kenichi pozostał przy japońskiej diecie.

Ohtaki maraton nie był zbyt ciekawy ani wymagający.

Na pocieszenie każdy zawodnik otrzymał bilet wstępu do miejscowej łaźni.

Gdy zacząłem pakować do plecaczka ręcznik i przybory toaletowe, Kenichi zaprotestował – w łaźni dostaniesz wszystko, czego potrzebujesz.

Rzeczywiście dostałem – ręczniczek o wymiarach 15 cm x 15 cm.

Naśladując miejscowych rozebrałem się do naga, położyłem ręczniczek na głowie i wyszedłem do ośnieżonego ogrodu. Dookoła głęboki śnieg, na szczęście ścieżka dla gości była przykryta plastikowymi matami. Gwiazdy błyskały na czystym niebie, w dali ośnieżone góry.

Widoki zapierały dech…. a może to mroźne powietrze stawało kością w piersiach.

Szybki prysznic i plusk do gorącej wody.

Po długim moczeniu się przyszła pora na końcowe ablucje.

W sali było wiele pryszniców, umieszczonych na wysokości około półtora metra, pod każdym prysznicem był niski stołeczek do siedzenia. Na półce stały butelki z szamponem i płynem do kąpieli.

Po wymyciu się w ruch szedł ręczniczek.

Oczywiście był on za mały żeby się nim do sucha wytrzeć.

Należało się trochę wytrzeć, wyżąć ręczniczek, trochę wytrzeć… i tak w kółko.

W którymś momencie zgubiłem się, czy ja się jeszcze wycieram po kąpieli czy może po spoceniu od wyżymania ręczniczka?

Kolejny dzień – jazda pociągiem do Biei gdzie odbywa się Miyasama Marathon.

Na dworcu w Biei czekał na mnie przedstawiciel organizatorów z tłumaczką – Mitsuko.

Na mój widok nie mogli ukryć rozczarowania.

Starszy, siwy, człowiek z wyraźnymi oznakami przemęczenia (dwa maratony i wyżymanie ręczniczka).

Pojechaliśmy do hotelu – bardzo komfortowy, wyraźnie ukierunkowany na narciarzy zjazdowych.

Mitsuko przedstawiła mi rozkład dnia: śniadanie, samoobsługa, od 7 do 9, lunch, to samo, od 12 do 2, obiado-kolacja – 7 – obługa przyniesie ci do pokoju.

Czy masz jakieś specjalne wymagania lub pytania, tu nikt nie zna angielskiego, więc lepiej jak powiesz teraz.

– Trasy biegowe? Widziałem z samochodu przystanki autobusowe. Jak mogę tam dojechać?

O 10 rano będzie na ciebie czekał autobus i zawiezie cię na trasę. Jak dojedziecie, to napiszesz na śniegu o której kierowca ma cię podebrać.

– Smarowanie nart, pewnie jest tu sala do smarowania.

Mitsuko przetłumaczyła pytanie kierownikowi hotelu, wyraźnie go to zakłopotało.

– Nie, nie ma sali do smarowania. Narciarze zjazdowi tego nie potrzebują. Konkretnie – czego potrzebujesz?

– Stołu z dostępem do gniazdka elektrycznego. Podczas smarowania powstaje masa ostróżyn parafiny, a więc dobrze, żeby pod stołem była jakaś plastikowa płachta, z której można te okruchy strząsnąć do śmieci.

Mitsuko przetłumaczyła, kierownik zapewnił, że stanowisko przygotują przed wieczorem.

Szybko wrzuciłem bagaże do pokoju i pojechałem na trasę biegową.

Śnieg, trasa i widoki dookoła były bajeczne.

Gdy wróciliśmy do hotelu, zauważyłem jakieś zamieszanie wokół maszyn do gier hazardowych.

Za kilka godzin wyjaśniło się – odłączyli i przesunęli je, aby postawić tam stanowisko smarowania nart.

W pokoju znalazłem bardzo eleganckie kimono i dokładną instrukcję jak rozpoznać i jak się zachować podczas trzęsienia ziemi, które są częste w tej okolicy.

W przeddzień wyścigu odbyła się kolacja dla zawodników zza granicy, którą zaszczycił swą obecnością książę Tomohito, główny sponsor maratonu – KLIK.

Wyznam, że książę wyglądał groźnie, zauważyłem że osoby, które do niego podchodziły, kłaniały się w pas. Książę głównie interesował się niewidomymi narciarzami, których było całkiem sporo.

Wyścig – nie był zbyt emocjonujący.

Ciekawsza była ceremonia zakończenia, na której każdy uczestnik otrzymał nagrodę – kilogram japońskiego ryżu. Najciekawsze było jednak to, że Australijka, Jenny Altermatt, wygrała wyścig w kategorii kobiet, pokonując znacznie od siebie młodsze Japonki.

Nagrodę wręczał książę Tomohito.

Na początku pewna konsternacja – nagrodą był puchar przechodni, czyli zdobywca pucharu musi za rok oddać go organizatorom.

Organizatorzy uznali, że nie mogą tego wymagać od Jenny, w związku z czym miejscowy jubiler już zaczął robić dla niej miniaturę pucharu.

Dodatkowa nagroda dla zwycięzcy to 10 kilogramów japońskiego ryżu.

Nie wspomniano, czy organizatorzy zapłacą za nadbagaż.

P.S.

Kilka miesięcy później otrzymałem list od organizatorów Sapporo Maraton.

Dziękowali za udział, zapraszali na następny rok i informowali, że pozwolili sobie wykorzystać mój wizerunek do promocji swojego wyścigu w roku 1998.

Ja – ten w czerwonych spodniach, tych samych co na starcie.

Monika Wrzosek-Müller

Neue Räume in Warschau

Eigentlich hatte ich vor, in Warschau lange Spaziergänge zu meinen alten, aber auch den neuen Orten zu unternehmen. Doch die Tage sind zu kurz, auch es ist zu dunkel, das Wetter spielt manchmal völlig verrückt; es gibt Schneegewitter oder Hagelstürme, dann scheint plötzlich die Sonne und mich überfällt eine Lethargie, die ich erst einmal überwinden muss, bevor ich mich überhaupt in Bewegung setzten kann. Sich aus dem geschützten und noch sehr altmodischen Viertel Saska Kępa in die Großstadt zu bewegen, erfordert Mut; hier ist alles klein, bekannt, überschaubar; drei größere, vertikal verlaufende Straßen und etwas mehr horizontale. Natürlich findet man auch hier schöne alte Bauhaus-Häuser, noch nicht herausgeputzt, noch im Urzustand, die mich anlächeln. Manchmal verfehlen die allzu pingeligen Renovierungen ihr Ziel, sie lassen die alte Patina verschwinden, zusammen mit der Schönheit und Einfachheit, zu schade. Doch die große neue Welt befindet sich eindeutig außerhalb von diesem Viertel.

Vor ein paar Tagen habe ich mich dann doch rausgewagt und bin in andere Räume, Stadtteile von Warschau aufgebrochen, eigentlich ganz im Zentrum, wohin ich früher nie vorgedrungen war. Der Raum hinter dem Zentralbahnhof, hinter der Shoppingmall „Złote Tarasy“, voll von richtigen Wolkenkratzern, Hochhäusern und mit ganz breiten geraden Straßen, hat mich erstaunt. Es ist da so viel entstanden, ganz neue Viertel, die für mich eher nach einer Metropole in Amerika aussehen und dem mir unbekannten New York als nach dem mir bekannten Warschau. Umso mehr freute ich mich, als ich die alten, gerade renovierten Gebäude der Norblin-Fabrik von weitem sah. Sie bilden einen schönen Kontrast zu der übrigen Bebauung in der Gegend. Eigentlich müssten wir in Europa doch aufpassen, nicht überall dasselbe zu produzieren und zu reproduzieren, dieselben Glasfassaden mit den schnell sich bewegenden Liften draußen, alles hochmodern und zugleich eher unmenschlich, so dass das individuelle Gesicht einer Stadt völlig verschwindet. Am „Rondo ONZ“ wehte der Wind so stark, dass viele Leute ihre ursprüngliche Route aufgaben und umkehrten; ein Mann im Rollstuhl wäre fast auf die Straße geweht worden, wären da nicht zwei kräftige junge Männer gewesen, die ihm halfen.

Endlich aber war ich doch bei der Norblin-Fabrik, Gebrüder Buch und T. Werner, angelangt und bewunderte erst einmal von außen das sehr schöne Objekt, das sich über mehrere alte Fabrikgebäude erstreckt mit den integrierten Bürotowern dazwischen. Von weiten sieht man schon ein nicht allzu buntes Murale von Pola Dwurnik, das die Fabrik darstellt und im Stil ihres berühmten Vaters, einen Maler, gehalten ist. Die Wahl der Materialien bei der Instandsetzung der Fabrik hat mich begeistert, neben edlen Holzarten gibt es Rosteisen [oxidierten Stahl], schöne Steinfußböden mit eingelassenen alten Schienenresten, die schöne Muster auf dem Boden bilden. Alles ist sehr elegant, präzise und in guter Harmonie zwischen der alten und modernen Struktur eingerichtet. Revitalisiert wurden insgesamt 9 alte Gebäude, die auch Baudenkmäler sind, sowie 50 Maschinen aus dem alten Maschinenpark, die im ganzen Gelände ausgestellt stehen, z.B. eine hydraulische Presse, die 50 Tonnen wiegt. Manche der Maschinenteile wurden ihrer ursprünglichen Funktion enthoben und fungieren z.B. als Untersätze für die Glastische, für die Bänke. Manche von den Gebäuden wurden komplett neu, aber in historischer Gestalt wiederaufgebaut.

Die Geschichte der Familie ist bemerkenswert: der Sohn eines Zeichners und Malers Warschauer Motive, des Franzosen Jean Pierre Norblin de la Gourdine, Aleksander Jan Konstanty Norblin, genannt John, geboren 1777, wurde nach langer Ausbildung in Paris zum Metallgießer (Bronze) nach Warschau angeworben und gründete dort 1820 die Norblin-Fabriken, damals „Warszawska Fabryka Bronzów“ (Warschauer Bronze-Fabriken) genannt. Sie produzierten hauptsächlich künstlerische Objekte in Bronze, z.B. große Leuchter für Kirchen, Epitaphien, auch Büsten. Er arbeitete viel für die Familie Czartoryski, fertigte eine Büste des Fürsten, auch Figuren und Ornamente für die Gräber der ganzen Familie. Erst später begann die Fabrik, auch Alltagsgegenstände wie Besteck etc. herzustellen. Die Fabrik wurde immer größer, fertigte auch die Samoware für russische Adelige; die Nachfrage nach den schönen, edlen Gegenständen stieg ständig, so wundert die Größe des Terrains, das die Fabrik einnahm, nicht. Auf dem Gelände befindet sich jetzt auch ein Museum, das die Firmengeschichte dokumentiert.

Noch sind nicht alle Räume in der Fabrik fertig und belegt, das Gelände wurde erst Ende September 2021 eröffnet; doch jetzt schon kann man sehen, dass es eine gelungene Mischung von Kunst bietet: zwei Galerien, Kultur, ein sehr luxuriöses Kino, „Kinogram“, mit einer noch moderneren Bar, mit mehreren Kinosälen, ein Bereich für eine Bio-Markthalle, „Biobazar“, wo man frische Bioprodukte kaufen und auch essen kann, und ein ganz großer Bereich für eine Food Town mit 23 gastronomischen Konzepten aus Europa, und anderen Teilen der Welt, wo man in geräumigen Fabrikhallen gut essen kann. Hier ist auch eine wunderschöne Piano-Bar untergebracht mit einer Bühne für die live-Musik und Tanzflächen.

Ich schlenderte langsam durch das ganze Gelände, das noch nicht überlaufen ist, und irgendwann gelangte ich in den ersten Stock mit einer wunderschönen Ausstellung in geräumigen, sehr gut designten Vitrinen, die aus den alten historischen Wagen der Fabrik gefertigt sind: die ganze Produktion der Fabrik von silbernen und versilberten Objekten; wir sehen Vasen, Platten, Besteck, Kelche, Kannen, Unterteller, Silberringe, Zuckerdosen, überhaupt Dosen etc… Großer Beliebtheit erfreuten sich kleine Tischbürsten mit ebenso kleinen, schön verzierten Schaufelchen. Ich erinnere mich an die alten, halb „aufgegessenen“ Löffel, die meine Oma in ihrer winzigen Wohnung in Mokotów noch benutzte und die sie über die Verbannung nach Kasachstan bewahrt und dann mit zurückgebracht hatte. Mit den Löffeln konnte man nichts mehr essen, die Versilberung war gesprungen, sie kratzten und man konnte sie nicht mehr richtig reinigen. Das meiste Silber war natürlich da, in der Verbannung, verkauft oder in Essbares eingetauscht worden; geblieben waren für uns Enkelkinder Erinnerungen wie: „das war doch echtes Norblin, oder eher Fraget“. Meine Oma schätzte die Erzeugnisse dieser polnischen Fabriken sehr und sie erzählte mir, dass in dem Flügel, den sie in ihrer Wohnung in Lemberg hatten zurücklassen müssen, drei Komplette von je 24 Besteckteilen für jede ihrer drei Töchter eingelagert waren; sie konnten nicht so viel in die Verbannung mitnehmen. Als ich vor ein paar Jahren in Lemberg war, auch in ihrer Wohnung, zwar verkleinert, denn da wohnten nun drei Familien, konnte ich keinen Flügel ausfindig machen, geschweige denn die Besteckkomplette für die Mädchen.

Die Norblin-Fabrik scheint mir eine Mischung aus Zukunft und fortgesetzter Vergangenheit in diesem während des Zweiten Weltkrieges wirklich total zerstörten Warschau zu sein. Im Sommer wird sich der Ort bestimmt mit Tausenden von Besuchern füllen.

By Patricia Claus

A spectacular Greek necropolis complex at Sanita, just outside Naples, will open to the public later this year, when the world will finally be able to see the stunning tombs that were carved into the volcanic tufa rock by the ancient Greeks who colonized the area.

Just outside the walls of Naples — originally named Nea polis, or New City, by the Greeks — the tombs were first discovered by accident in the 1700s. Since that time they have variously been forgotten, partially uncovered and then opened to a very small number of people who were friends of the aristocratic family who owned the palace that was built atop them.

Now, however, they are being systematically excavated and restored, thanks to a woman who married into the family, who petitioned for the site to be overseen by Italy’s Central Institute for Conservation (ICR).

According to a report in Smithsonian Magazine, workers most likely discovered the tombs way back in the 1700s, when a hole they made in the Palace’s garden above destroyed the dividing wall between two of the necropolis’ chambers.

Lying forgotten again for another century, they were rediscovered in 1889, when Baron Giovanni di Donato, the ancestor of the current owner of the Palace, excavated his property to try to tap into a water source for his garden.

The necropolis had been used by the Romans after the time of the Greeks, but the area was subject to flooding and it was eventually buried in feet of sediment. The sarcophagi the Baron found in the 1800s lie 40 feet below street level now.

The spectacular necropolis contains dozens of rooms that are cut as one piece into the volcanic tufa — the same stone which the Roman catacombs were carved out of.

Two years ago, Luigi La Rocca took the reins at the Soprintendenza, a government department which oversees Naples’ archaeological and cultural heritage. The Greek necropolis was one of the first places he visited. From that time onward, he has made it his mission to open up the spectacular Greek necropolis to the public.

“The tombs are almost perfectly conserved, and it’s a direct, living testament to activities in the Greek era,” La Rocca adeclares, adding “It was one of the most important and most interesting sites that I thought the Soprintendenza needed to let people know about.”

Just as they did elsewhere, the Romans revered Greek culture to the point that they allowed the Greeks whose ancestors had settled the area to continue their lives and practice their culture in every way.

These Greeks built stunningly ornate family tombs, placing multiple bodies in each tomb, presumably all the individuals belonging to one family.

Archaeologists at the Soprintendenza believe that the necropolis was in use from the late fourth century BC to the early first century AD. With its discovery and restoration, La Rocca says that it is now “one of the most important” archaeological sites in Naples.

Another Greek funerary complex, at the nearby Greek colony of Posidonia — later called Paestum by the Romans — also features spectacular artwork, including the only known representational fresco to survive from the time of Ancient Greece, showing the deceased as a young man diving into the sea.

Of course, the area is also not far from the sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which were covered by feet of ash in the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD.

The Via dei Cristallini, the Neapolitan street on which the aristocratic di Donato family’s 19th-century palace was built, gives its name to the necropolis, which is referred to as the “Ipogeo dei Cristallini.”

Each tomb has an upper chamber, where funerary urns were placed in niches above benches that were carved into the rock for mourners. The bodies of the dead were placed in the lower burial chamber. But both chambers were richly decorated, with statues — which archaeologists believe may have been of ancestors — as well as sculpted eggs and pomegranates, which are both symbols of new life and resurrection.

Astonishingly, the names of the dead themselves may also be preserved on the walls of the tombs, with the ancient Greek writing still clearly visible.

“The incredible thing about this site is that it was all ‘scavato’ — excavated,” says Melina Pagano, one of the restorers of the necropolis. “They didn’t take the (stone) beds and put them there — they carved (the room and its contents) from the hillside.”

Perhaps most incredibly of all, the beds that the bodies once lay on had integral carved stone pillows that look completely lifelike, as if they are made of down.

Unlike the Roman catacombs, which were carved out of the tufa by ordinary people in an effort to make a suitable burial place for the early Christians, the tombs of the necropolis at Ipogeo dei Cristallini were expertly carved by skilled professionals and boast a wealth of colorful frescoed garlands, and even trompe l’oeil paintings.

One jaw-dropping view greets visitors to the necropolis when they enter one room, which is presided over by the Gorgon Medusa, whose job it is to scare off all the evil spirits who might disturb the souls of the deceased.

The survival of the necropolis complex is for the most part due to the care of the di Donato family, whose scion first had the necropolis excavated in the 1800s — at which time many of the objects found were removed and taken to the Museum National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN) and the Soprintendenza.

Numbering approximately 700, they have been displayed at the Museum ever since that time. Some other objects from the necropolis are also in the collection of the family as well.

It was the Baron who had the staircase built that takes visitors down into the necropolis; at the time, he invited local historians to survey the site and record descriptions of the tombs’ frescoes, which have tragically deteriorated since they were discovered.

This was also when the skeletons of the dead were removed from the necropolis — although there are pieces of bones there even today in some areas; these will undergo study before the remains are respectfully interred elsewhere.

After the flurry of activity in the 1800s, the ancient Greek necropolis once more became lost to the world outside of the sphere of the di Donato family; for 120 years they lay untouched behind a locked door in the Palace’s courtyard. No one from the general public ever knew about or was allowed to enter the area.

But that all changed, courtesy of Alessandra Calise Martuscelli, who married into the family.

“Twenty years ago,” she tells interviewers from the Smithsonian, “we went to the MANN to see ‘our’ room (where the Cristallini finds are exhibited), and I was overcome with emotion. It was clear that it was important to open it.”

Calise, who is a hotelier, and her husband Giampiero Martuscelli, an engineer, successfully applied for regional governmental funding and oversight for the necropolis in 2018. Federica Giacomini who supervised the ICR’s investigation into the site, is effusive regarding the priceless frescoes in the necropolis, stating “Ancient Greek painting is almost completely lost — even in Greece, there’s almost nothing left.

“Today we have architecture and sculpture as testimony of Greek art, but we know from sources that painting was equally important. Even though this is decorative, not figurative painting, it’s very refined. So it’s a very unusual context, a rarity, and very precious.”

Paolo Giulierini, the director of the MANN, who is also responsible for the priceless treasures at Pompeii, is keenly appreciative of the immeasurably important Greek cultural heritage of Neapolis as a whole. Despite the historical riches of Pompeii and Herculaneum he believes that Neapolis was “much more important” than they ever were, as a center of Hellenic culture that “stayed Greek until the second century CE.”

Moreover, the museum director believes that the Ipogeo dei Cristallini tomb complex compares only to the painted tombs that were found in Macedonia, the home of Philip II and Alexander the Great; he states that he believes they were “directly commissioned, probably from Macedonian masters, for the Neapolitan elite.

“The hypogeum teaches us that Naples was a top-ranking cultural city in the (ancient) Mediterranean,” Giulierini adds.

Tomb C is the most spectacular of all the four chambers which will open to the public this year. With fluted columns flanking its entrance, the steps leading down to its entrance are still painted red. Six sarcophagi, carved out of the bedrock in the shape of beds, feature “pillows” that still have their painted stripes, in hues of yellow, violet and turquoise; incredibly, the painter even added red “stitches” in the “seams” of the pillows.

The pigments used in these elegant sarcophagi are remarkable in themselves, says restoration expert Melina Pagano, pointing out the Egyptian blue and ocher used on the pillows, as well as the red and white painted floors and legs of the sarcophagi.

Pagano and her team at the ROMA Consorzio used a laser to clean small sections of the stone pillows.

While the only object not carved out of solid rock in the chambers is the life-sized head of Medusa, made from a dark rock, possibly limestone, and hung on a wall opposite the door, it is perhaps the most stunning individual object of them all in the necropolis, looking out on us today with a fearsome gaze across the millennia.

Ein paar Eisenbahn-Nerds haben errechnet, dass man dank der neuen Eisenbahn zwischen Laos und China nun von Portugal nach Singapur durchgehend mit dem Zug reisen kann.

18.755 Kilometer in 21 Tagen, von Südeuropa bis an die Südspitze der Malaiischen Halbinsel, alles mit dem Zug: Nach Ansicht von Experten wurde ein neuer Rekord für die längste ununterbrochene Bahnfahrt aufgestellt. Selbstverständlich handelt es sich dabei nicht um eine Direktverbindung.

Möglich ist dieser Megatrip, weil Anfang Dezember 2021 China die erste Teilstrecke der “Neuen Seidenstraße” durch Südostasien eröffnet hatte. Nach fünf Jahren Bauzeit wurde der rund 400 Kilometer lange Streckenabschnitt zwischen der laotischen Hauptstadt Vientiane und der chinesischen Stadt Kunming fertiggestellt: Über den Grenzbahnhof Boten werden Vientiane und Kunming über 242 Tunnel und Brücken durch bergiges Terrain verbunden.

Die Anbindung von China an Laos ermöglicht nun die wohl längste Zugverbindung der Welt, wie es Reddit-Nutzer gemeinsam mit dem britischen Eisenbahn-Enthusiasten Mark Smith ausgerechnet haben: Start der Rekordreise ist die Stadt Lagos in der Algarve im Süden Portugals. Weiter geht es über das französische Hendaye im Baskenland und über Paris nach Moskau.

Mit der berühmten Transsibirischen Eisenbahn geht’s weiter bis nach Peking. Kurzer Zwischenstopp in Kunming – der Hauptstadt der chinesischen Provinz Yunnan –, und weiter geht die Reise in die laotische Hauptstadt Vientiane. Über Bangkok und die drei malaysischen Städte Padang Besar, Penang und Kuala Lumpur erreicht man schlussendlich nach mindestens dreiwöchiger Reisedauer Singapur.

Auf der Route müssen Reisende in Lissabon, Madrid und Paris jeweils einmal und in Moskau und Peking zweimal übernachten, um die weiteren Anschlusszüge zu bekommen. Bei fünf so spannenden Hauptstädten sind diese Stopps aber wohl eher als eine Bereicherung zu sehen.

Die Kosten für eine Fahrt auf der längsten Bahnstrecke der Welt belaufen sich laut “Daily Mail” auf etwa 1.200 Euro – in eine Richtung.

Henry Wismayer

A month before I boarded the plane to Cairns, Fox Studios had released The Beach (2000) into cinemas. Based on the bestselling 1996 novel by Alex Garland, and directed by Danny Boyle, the film follows Richard (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) on a backpacking journey to Thailand. After drinking some snake blood, he finds his way to a secret island, where an idyllic community lives beside a pristine island lagoon. There he finds joy and love to the ambient strains of Moby’s ‘Porcelain’ (2000), then fucks it all up, and goes insane.

I’d watched the film in a bar in Bali. In those days, backpacker bars throughout Southeast Asia would often show flickering, pirated copies of the latest cinema releases. But I didn’t pay much heed to its allegorical warnings about the dangers of surrendering to serendipity, or its blunt moral that paradise could only ever be ephemeral. I was 19 years old, and preoccupied with finding my own.

‘Mine is the generation that travels the globe and searches for something we haven’t tried before,’ says Richard. ‘So never refuse an invitation, never resist the unfamiliar, never fail to be polite and never outstay the welcome. Just keep your mind open and suck in the experience.’

New experiences have a mnemonic quality – they create a more lasting imprint in the brain

At the end of my own first brush with this zeitgeist, I came home armed with what amounted to a Proustian epiphany: I had come to realise, with a certainty that brooked no contradiction, that fresh experiences emblazoned themselves in the mind at a higher definition, palpably lengthening time. If memories of home-life often seemed diffuse, its events overlapping and abbreviated by familiarity, the ones I carried back from Bangkok were pin-sharp.

Would it make sense if I told you that I can conjure every hump and hollow of that Thailand beach? I can tell you the sand was the colour of bleached coral, that it was fringed with a tangle of low-slung mangroves. I remember that we had just descended from that boulder when it began to rain, and that we hopscotched around washed-up flotsam, drenched to the skin. I can recount how the frothing ebb tide had left dozens of jellyfish stranded every few yards, some of which we attempted to flick back into the surf with a stick, an act which I now realise probably looked thuggish to any bystanders, though I promise it was charitably intended. Later that day, we sat on the beach and watched lightning fork across the sky, except on the horizon, where the dusk broke through in a fan of sunbeams, making silhouettes of the container ships far out to sea.

Possible explanations for the pellucid nature of such recollections are not confined to the philosophical. In recent years, neuroscientists have discerned a clear correlation between novelty and memory, and between memory and fulfilment. Their findings suggest that new experiences have a mnemonic quality – they create a more lasting imprint in the brain. It didn’t seem an unreasonable leap of logic to assume that this might come to be seen as retrospective proof of a person’s rich and happy life.

I recently happened across a multinational study, undertaken in 2016, which investigated the link between novel experiences and the potency of memory. The authors set up an experiment in which mice were introduced to a controlled space and trained to find a morsel of food concealed in mounds of sand. Under normal conditions, researchers found that the mice were able to remember where the food was hidden for around one hour. However, if the environment was altered – in this case, the mice were placed in a box with a new floor material – they could still find the food up to 24 hours later. The introduction of new conditions appeared to magnify the creatures’ power of recall.

Employing a technique known as optogenetics, the study attributed this phenomenon to activity within the locus coeruleus, a region of the mammalian brain that releases dopamine into the hippocampus. Novel experiences, the results seemed to indicate, trigger happy chemicals, which in turn help to produce more indelible engrams, the biochemical traces of memory.

It was with an intuitive version of this self-knowledge that I forged out into the world: a mouse forever in search of a new floor. I spent the years after university shaping my ambitions around overseas adventures, and the months in between desperately saving for the next. Travel writing seemed an obvious alibi, a means of camouflaging my experiential hunger with a veil of purpose. But, in reality, I was engaged in a personal mission to see everything, and I was in a hurry.

My travelling assumed a frantic cadence, as if movement between map pins was a competitive sport. I would travel to the limits of my courage and energy, crisscrossing remote hinterlands, clambering from one clapped-out bus to another, often on no sleep. If I had any particular travelling sensibility it approximated Robert Louis Stevenson’s epigram: ‘I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move.’ It was never my intent to check off a list of sights and animals; this wasn’t some Instagrammer-style process of acquisition and display, at least not explicitly so. More, it was born of a will to reset the view, like an impatient child hitting the lever on a 1980s View-Master, desperate to change the slides.

Ironically, this often placed me in harm’s way. In the Brazilian Amazon, for instance, I was almost killed by a four-year-old child. A hunter had left a loaded shotgun in a dugout canoe, its muzzle resting on the bow, only for his daughter to mistake it for a plaything and pull the trigger. I can still remember the sensation of the buckshot wafting past my abdomen, and wondering out loud, minutes later, how far it might have been to the nearest hospital. (‘Eight hours by outboard motor,’ our teenage guide replied gravely.)

In 2010, I contracted typhoid, dengue fever and bilharzia, in the space of six months. The last of these, a parasitic disease endemic to the Great Lakes region of central Africa, didn’t make itself known until four years later, when streaks of blood in my urine betrayed the Malawian stealth invaders that had been loitering and multiplying in my bladder all that time.

But the perils inherent in my reckless movement always receded after the fact. Often, the close shaves themselves became rose-tinted in the retelling, as if every misadventure was further evidence of my enviable, halcyon life. The perils burnished the story I was writing. It was all part and parcel of the experientialist’s covenant. Again, from Richard in The Beach: ‘If it hurts, you know what? It’s probably worth it.’

As travel democratised, a consensus grew that a storied life must necessarily be a well-travelled one

My symptoms may have been specific and acute, but my choice of remedy for existential anguish was by no means mine alone. In hindsight, I realise I was merely a fanatical disciple of a widespread impulse. For me and many other cynical agnostics, novelty had become the stuff of life. As organised religion waned and we turned away from metaphysical modes of being, experience presented itself as a surrogate for enchantment.

The Western democracies were set on their trajectory: more consumption, more capitalism, more privatisation, which for most people seemed to promise a half-life on a treadmill of work, anxiety and inflexible social norms. But the outside world offered a way out. Only by fleeing the geographical constraints of that staid order was it possible to apprehend its shortcomings – to discover the ways that our own status quo, in its hubristic embrace of what we deemed progress, might have been haemorrhaging precious truths. The Western traveller’s existential epiphany – that pastoralists in the foothills of some impoverished Asian hinterland seemed more at peace with the world than whole avenues of London millionaires – may have been hackneyed and condescending. But to a 20-something in the early 2000s it felt profound. And so we came to see a full passport as a testament, not just to a life well lived, but to some essential insights into the human condition.

Of course, the travel itself had become so easy. The proliferation of new long-haul airlines, often subsidised by vain Middle Eastern plutocrats with bottomless pockets, ensured that transcontinental fares got lower by the year. The no-frills revolution, pioneered by the likes of Easy Jet and Ryanair, transformed the once fraught and expensive decision of whether to go abroad into a momentary whimsy. A weekend in Paris? Rome? Vilnius? Now $60 return.

For my generation, this revolution of affordability and convenience was providential, coinciding with a time in life when we had the paltry wages and an absence of domestic responsibility to exploit it. The collapse of the old Eastern bloc, and its constituent nations’ subsequent tilt towards consumer capitalism, opened up the half of my continent where the beaches weren’t yet overcrowded and the beers still cost a dollar. In the meantime, the communications revolution meant that organising such trips had never been more straightforward. One spring, I arranged for a few friends to climb a Moroccan mountain over a long weekend. We flew to Marrakesh on the predawn flight from Stansted Airport in London, where a dozen stag dos, bound to exact a very British carnage on Europe’s sybaritic capitals, were sculling tequila shots at 5am. Twelve hours later, we were 10,000 feet up in the High Atlas, readying ourselves for a 1am summit assault of Jebel Toubkal. I remember lying in the base-camp dormitory, giggling at the music of our farts brought on by the rapid change of air pressure, in a state of exultation. This kind of instant adventure, unimaginable just a decade earlier, was now just a couple of days’ wages and a few mouse clicks away.

As travel democratised, and became a component of millions more lives, a consensus grew that a storied life must necessarily be a well-travelled one. Holidays were no longer an occasional luxury, but a baseline source of intellectual and emotional succour. This idea of travel as axiomatic – as a universal human right – was a monument to an individualist culture in which the success or otherwise of our lives had become commensurate to the experiences we accrue.

And I was there, an embodiment of this new sacrament, and its amanuensis. In the proudest version of my self-image, I was a swashbuckling, bestubbled wayfarer, notebook in hand. ‘The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation,’ wrote Henry David Thoreau. Not me, no sir. Because I was a man who had been to 100 countries. Who knew what wonder was, and where to find it.

A decade or so ago, when I was approaching my 30th birthday, I went on a writing assignment to the Indian Himalayas, where I trekked for two weeks through the most beautiful countryside I have seen, before or since. I had a guide, a gentle man called Biru, and we spent most of the days walking in each other’s bootprints, chatting about the geography, the culture of the Bhotia people we encountered in the foothills, and the contrasts between our disparate lives. But one afternoon, on the approach to a 14,000-foot saddle called the Kuari Pass, I felt buoyed by some hitherto untappable energy, and I left Biru far behind.

As I ran, zigzagging up the mule trails, I suddenly became gripped with an extraordinary lucidity. It felt as if only now, with the last vestiges of civilisation 12 miles down the mountainside, did I have the solitude with which to grasp the true splendour of my surroundings. As I clambered from joy into reverie, a vision kept entering my consciousness – of a broad-shouldered man, beckoning me forward.

He sat on the pass, back propped against a hump of tussock grasses. He was just as the most precious family photos recalled him: the same age I was now, lean and smiling, in faded jeans and the threadbare grey T-shirt he wore on a sunny day in a south London park before he fell ill. He looked strong – not ghostly, but corporeal – and I remember being struck that he could look so beatific up there, seemingly inured to the brittle wind whipping up from the valleys below. I had a vague sense that if only I could get there, to the pass, we could stand shoulder to shoulder, and all the secret knowledge I had been denied – of how to live the life of a good man, of how to live unafraid – would flow from him into me.

At dusk, encamped at the base of the final approach to the pass, I felt hollowed out, bereft. After we pitched our tents, I walked a mile back down the trail and found a peaceful spot in a glade of tall deodar cedars, where I wept about my dad for the first time in years.

My most distressing childhood memories were, in fact, lurid dramatisations of events I’d never witnessed

In his book The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), Sigmund Freud described the death of a father as ‘the most important event, the most poignant loss in a man’s life’. I don’t know if that’s true. But I think I have always known that the first waymarker on my trip around the physical world was the same moment that upended my private one. According to the death certificate, that was at 10:30pm on 13 March 1985, when my father succumbed to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in a London hospital, at the age of 32. Right from the start, the trauma of this event corrupted the way I processed and recalled experiences. Henceforward, my hippocampus would be a faulty and elastic device. I was four years old at the time of my father’s death. But I have no concrete memories between then and the age of eight.

Only in more recent years, in conversations with my mum, would I come to realise that my most distressing childhood memories – that is to say, those of my dad’s actual demise – were, in fact, recurring nightmares, lurid dramatisations of events I’d never witnessed. In the most indelible, I walk into a room of starkest white, my childish rendition of a hospital. Over in a corner, he lies dead and shrunken on a plinth. He has big purple welts over his eyes, like a melancholic clown. I can conjure this image with crystal clarity, yet my mum insists I was never exposed to his diminishment at the end, let alone his body when the fight was done.

Of the man as he was in life there is next to nothing. Just a sonorous voice, impossibly deep, my recollection of which is tactile as much as aural: a muscle memory of a reverberation I felt as I clung to his knees. What image I have stored has always been a spare composite, moulded around the gauzy recollections of those who loved him best. His friends and relatives would tell me: ‘Everyone adored Peter.’ And: ‘You are the spitting image of him,’ though this last wasn’t entirely true for, while I am tallish, he was a giant: 6 foot, 6 inches and broad, with feet so large he had to go to a specialist shop to buy his shoes. He was a sportsman, though one too laconic to take sports that seriously, and he was a talented artist, given to scrawling note-perfect caricatures on request. A self-possessed man, he had rebelled against the austere mores of a disciplinarian Maltese household, growing up to be kind, generous, egalitarian and wise. Oh, and he was also handsome, smart and preternaturally charming. An early death does not lend itself to balanced valediction, you see. Nonetheless, I was convinced of his perfection. Remember your dad: the fallen god.

This tendency to deify the absent parent – hyperidealisation – had left a haunting question unanswered: if the god was so mighty yet still succumbed, what hope was there for me? By all accounts, my perfect father had wanted nothing more than to live. It was fate, not choice, which had denied him that wish, and so I couldn’t trust fate at all.

I was in my mid-20s when I became convinced of the imminence of my death.

It would be too neat a story to suggest that I was always conscious of a direct causation between this dark fatalism and my early bereavement. As a child, fatherlessness was just the way of things, an ineluctable state of being which I accepted with the outward stoicism of one who knew no different.

However, as I neared the age he was when he died, I became transfixed by the expectation that my father’s destiny was mine as well. Just as I had internalised my relatives’ exhortations to step into his shoes – to be ‘man of the house’, custodian of my surviving family – I also expected to emulate his attenuated life-curve.

My days became backtracked by a hum of worry. I never saw anyone about it, and seldom if ever mentioned it to friends or loved ones. But reading around the edges, I suppose it resembled post-traumatic stress disorder, a miasma of intrusive thoughts, and vivid, almost hallucinatory, anxieties. At my most vulnerable, I felt hunted. Somewhere on the near horizon was a sickness, something to expose the weakness invisible to everyone but myself. I wasn’t sure what shape this chimera would adopt (probably cancer, in keeping with family tradition). But I knew it would be something enervating and rapid – a desperate withering. And I knew that I would make no peace with it, that I would endure every downward step in terror and the keenest fury at the injustice of it all.

Denied my precious years of formative complacency, knowing that it is all anguish and heartbreak in the end, I’d lit out to engrave my brain with random people and places, as if this alone were a barometer of self-worth. I might have kidded myself that it was just the pursuit of happiness. But, in reality, what I was embarking on was a project of temporal elongation, forestalling my death by bleeding each hour of moments. It just seemed like the best compensation for the years I was predestined to lose.

For the time that I lived in thrall to this self-inflicted prophecy, my overseas journeys provided respite for my restless mind. But the theatre of travel was changing, fast.

The paradigm shift made itself known in a new idiom: the ‘selfie’, bringing with it a disconcerting atmosphere of self-absorption to every tourist attraction and viewpoint in the world. ‘Digital nomadism’ debuted as an aspirational ideal, marketing the promise of professional success unconstrained by the geographical manacles of conventional, office-based work. The influencers hashtagged their way to fame and fortune. But somehow the transparency of their narcissism embarrassed whatever countercultural affect people like me were trying to cultivate. The retiree’s humble dream of saving for a ‘holiday of a lifetime’ had evolved into a ‘bucket list’, a life’s worth of checkable, brag-worthy aspirations. A poll in 2017 found that the most important factor for British 18- to 33-year-olds in deciding where to go on holiday was a destination’s ‘Instagrammability’.

Youth hostels that had once seemed like entrepôts of cultural exchange had instead come to feel like solipsistic hives, inhabited by people cocooned in the electric glow of phone and laptop screens. Travel had become egocentric, performative and memeified.

This new vulgarity appeared in tandem with travel’s exponential growth. The globalisation of English as a lingua franca was removing the enriching incentive to learn the local language. Smartphone maps meant you no longer had to ask strangers for directions. Sparking the locus coeruleus – triggering that synaptic lightning storm invoked by new experiences – had always been contingent on surprise. But now a glut of foreknowledge and the ease of forward planning was acting like a circuit breaker. What once seemed impossibly remote and enigmatic had been demystified. Pleasure cruises plied the Northwest Passage.

These reductive trends, both technological and cultural, were conspiring to dull the joy of visiting other places. The planet’s riches, which I’d once thought inexhaustible, seemed diminished, whittled down to a list of marquee sights, natural and human-made. Everything was too goddam navigable. Hell, perhaps I had just coloured in too much of the map.

It is perhaps indicative of my reluctance to plumb the origins of my travel addiction that it was only recently – while searching for some way to frame this idea of accumulating experience to fill a void – that I came across the work of Daniel Kahneman. An Israeli psychologist and Nobel laureate, Kahneman is renowned as the father of behavioural economics. The writer Michael Lewis calls him a ‘connoisseur of human error’. Some of his most intriguing theories have been in the field of hedonic psychology, the study of happiness.

Over decades of research and experimentation, Kahneman identified a schism in the way people experience wellbeing. In his bestselling memoir, Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011), he articulates this dichotomy in terms of the ‘experiencing self’ and the ‘remembering self’. The experiencing self describes our cognition as it exists in the ‘psychological present’. That present, Kahneman estimates, lasts for around three seconds, meaning an average human life comprises around 600 million of such fragments. How we feel in this three-second window denotes our level of happiness in any given moment.

The remembering self, by contrast, describes how the mind metabolises all of those moments in the rear-view mirror. The sensation resulting from this second metric would be best described, not as happiness, but rather ‘life satisfaction’.

Kahneman’s crucial observation was that the way we recall events is invariably divorced from the experience itself. One might expect the memory of, say, witnessing the Northern Lights to directly correlate with our feelings at the time – to comprise an aggregation of the experiencing self’s emotional responses to sensory stimuli. Instead, the remembering self is susceptible to all kinds of ‘cognitive illusions’. In its urge to weave discrete experiences into a desirable narrative, the memory will edit and elide, embellish and deceive. The actual sensations, and, by extension, our true sense of how we felt, are lost forever. We are left with only an adulterated residue. ‘This is the tyranny of the remembering self,’ Kahneman wrote.

The narcissistic atmosphere of the selfie age had exposed the solipsism of my own quest

This revelation held import for all manner of human experience. (Kahneman’s most famous illustration of the divergence was an experiment involving colonoscopies, which I will refrain from describing.) But it seemed to have particular implications for the valence of holidaymaking, and the travel-oriented ambitions I and others had opted to pursue.

For years, I’d been convinced that the mnemonic quality of novel experiences presented a route to happiness. The philosophy that I had come to live by – that chasing new horizons produced a more colourful tapestry in the mind, and that this could be cashed in for contentment – had seemed self-evident. But, according to Kahneman’s hypothesis, the calculus was at least partly illusory. Was experientialism a legitimate route to wellbeing? Or was it just a function of my storytelling impulse, my urge to portray my life as a battle to outrun a prophecy, and thereby prone to novelistic biases that I was helpless to regulate?

In the meantime, I knew, other important sources of happiness had been neglected. I had let friendships lapse. I had scorned any inclination to sustain a sense of belonging at home. I had driven my partner, Lucy, to distraction with my pathological need to shape the calendar, not to my mention my mood, around coming foreign capers. Yet I was no longer sure that I had been honest with myself about how necessary it had all been. I suspected that one of the reasons I was so disconcerted by the narcissistic atmosphere of the selfie age was that it had exposed the solipsism of my own quest. For while I balked at ‘influencer’ superficiality, I also appreciated that my travel writing was just a more sophisticated version of the same tendency. I wondered how many other people might have been using travel in a similar, medicinal way – to curate a narrative, sometimes at the expense of subjective joy.

It didn’t help that tourism was assuming more ethical freight. Renewed calls to decolonise the Western mind called into question the rich world’s entitlement to tramp through poorer lands. The relationship between travel and ecological destruction solidified. Air travel, in particular, dwarfed almost every other activity in terms of individual carbon emissions. Suddenly, there seemed to be an irreconcilable hypocrisy about someone who yearned to see the world, but whose actions contributed to its devastation.

By the time COVID-19 interrupted the trajectory, it was no longer possible to sustain the masquerade that travel was, by definition, an ennobling endeavour. The traveller had mutated from a Romantic ideal of human curiosity into something tawdrier: a selfish creature pursuing cheap gratification at the cost of everything. A mammal that fondled the coral reefs while driving the ocean acidification that could wipe them out. The desire to see foreign places had come to seem like just another insatiable and destructive human appetite, its most feverish practitioners a dilettante horde, pilgrim poseurs at the end of time.

There was no way to avoid a reckoning with the egotistical underpinnings of my own itinerancy. After all, what was I if not the archetype of the vainglorious traveller, a moment collector for whom learning and pleasure were incidental to my quest for affirmation? And, of course, I was an agent of the demystification and cultural homogenisation I deplored, writing about places that might have been better off left alone. (By this time, the Thai island where they filmed The Beach, a magnet for tourists after the film’s release, had been closed to visitors, a scene of ruin.) Journeys that once felt carefree were now tainted with remorse, as I realised that my dromomania could so easily be reframed as a kind of consumerist greed.

‘Every time I did these things, a question arose about the propriety of doing what I was doing,’ wrote Barry Lopez in Horizon (2019), his recent meditation on travel and natural communion. ‘Shouldn’t I have just allowed this healing land to heal? Was my infatuation with my speculations, my own agenda, more important? Was there no end to the going and the seeing?’

There seems no way of divining what will become of our compulsion to wander

Of course, there was an end, or at least a pause. A pandemic saw to that. The coronavirus lockdown, which came into force in my home country of England on 26 March 2020, precipitated the most static period of my adult life. But by then, truth be told, my manic period of travelling was already behind me.

If death had been the poisonous kernel of my fatalism, new life would provide a cure. My daughter, Lily, was born in 2012; a son, Ben, followed three years later. It is counterintuitive, I suppose, that the rise in stakes that attends a child’s dependence should have pulled me clear of anxiety. But then, too, parenthood brought with it an obligation to prioritise other lives over my quixotic search for self-validation. These years, during which I surpassed the age my father had been at the time of his death, provided milestones of a more meaningful escape.

Travel became less essential. I began to revisit places I loved and reconciled myself to the idea that there were places I would never see. I no longer slept with an envelope of travel documents – passport, bank notes, immunisation certificate – at my bedside. In this way, lockdown was a coda to a process of divorce already underway.