Alma Karlin’s travelling book, The odyssey of a lonely woman, was edited in English, by Victor Gollancz, London, 1933, it consists of reports about her journeys out of America, in the Far East and through Australia.

She was an Austrian, so it is why some her titles were published in German first, then translated into Slovenian. Many of them have not yet been published; they are kept in the National and University Library of Slovenia and in the Berlin State Library (according to Wikipedia in a building in Unter den Linden).

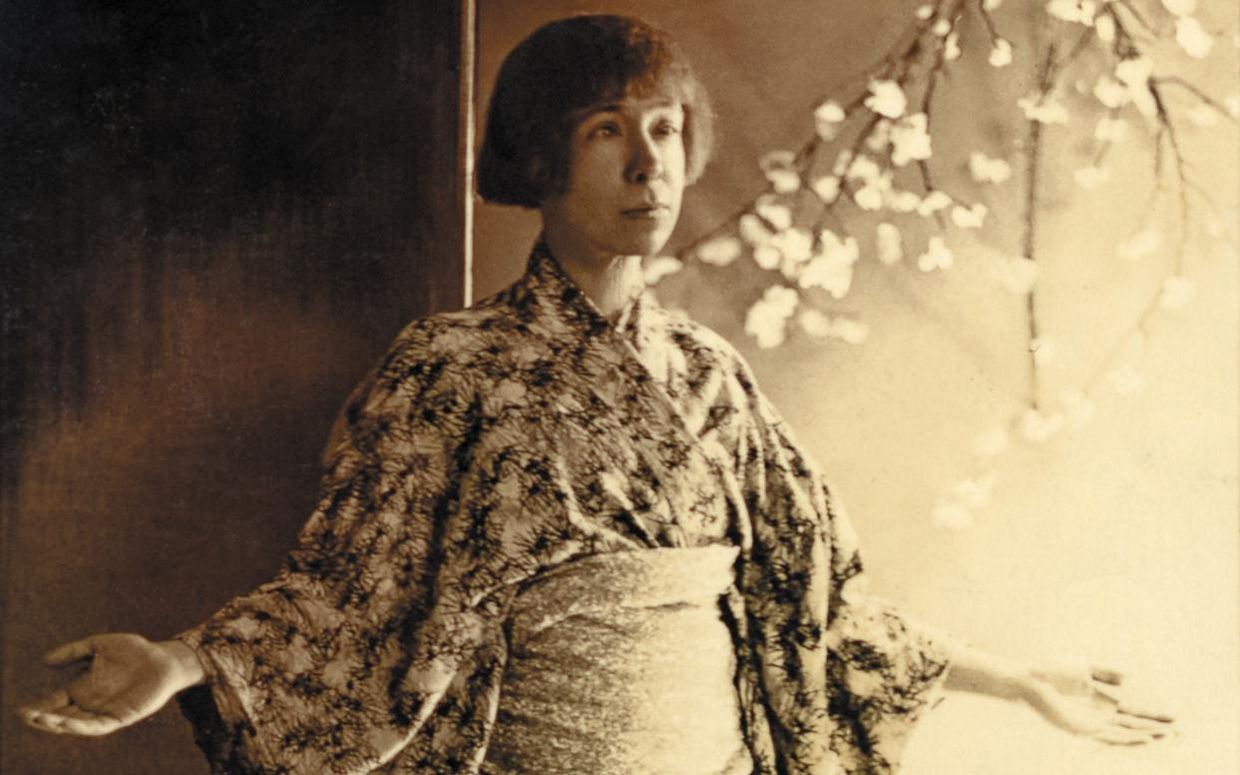

Alma Karlin (October 12, 1889 – January 14, 1950), was born in Celje, a small town, that time located in what is now Slovenia and was still part of the Habsburg monarchy. She was a Slovenian traveler, writer, poet, collector, polyglot and theosophist; the second European women to circle the globe alone. The first was Ida Pfeiffer, 100 years earlier.

Karlin spent her life trying to escape this political narrow-mindedness of her time. She studied several languages in London. She learned English, French, Latin, Italian, Norwegian, Danish, Finnish, Russian, and Spanish. In the later years, she also studied Persian, Chinese, and Japanese. And then also Esperanto. She invented and started work on her (unpublished) dictionary of ten languages, including Slovene. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Karlin had to move to Sweden and Norway; 1919 she returned home, to Celje, then already part of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. She planed her journey, but unlike most travellers of the time, she did not have sufficient financial means and had to finance the nine-year journey herself by doing various jobs. Among others, she opened a language school. She taught up to ten hours a day, doing in the same time also her painting and writing.

In 1919 she set off on a world tour. She visited South and North America, the Pacific Islands, Australia, and various Asian countries, inclusive India. The objects she collected during the journey, which are now in the Celje Regional Museum, reflect these changing financial possibilities. After her return, she lived in her native town until her death in 1950. She celebrated great success as an author and her books, which often had her world trip as a theme, were translated into numerous languages. Under the National Socialists, her works were banned and after 1945, as a German-language author, she was attacked by Yugoslavia and subsequently forgotten. Only in recent years has her work been rediscovered in and outside Slovenia.